When it comes to design, countryside houses needn’t be the poor relations to their urban cousins. Cheaper land prices mean more space to play with, some distance away from or even out of sight of neighbours, so architects can let their creative hair down. But there’s a risk to these upsides: period pastiches and extravagant flights of fancy can blight rural areas. Or as architect Friedrich Ludewig puts it: “If it’s a UFO that’s crashed into the field, people think it’s just someone rich showing off”.

More like this:

– Stunning outdoor spaces for all

– Design’s new stone age is here

– Dream homes from the past century

A growing number of contemporary architects are showing that there is another way. From a Costa Rican beach to the Kent countryside in the UK, houses are taking shape that are sensitive to local building styles, materials and topography – but are unexpectedly daring in their design.

Much of the exciting aesthetic happens when architects make the effort to get under the skin of the surrounding residential and farm buildings. That approach “helps to generate a new style that roots a house in that area”, says architect Rory Harmer, who has designed around a dozen new houses in the countryside.

The English county of Kent is peppered with old oast houses – conical buildings where hops were dried as part of the beer-brewing process. In the pretty village of Marden, Bumpers Oast by architecture firm ACME, is a 21st-Century reinterpretation of those ubiquitous structures. Rather than the typical brick walls and roofs of Kent peg-clay tiles, its five towers are covered in tiles of different shades – dark, earthy tones at the bottom rising to paler grey at the top – to create what ACME’s director Ludewig calls a “single unfolding volume”.

“It’s more contemporary, to play with one material rather than two,” adds Lucy Moroney, ACME’s project architect on Bumpers Oast.

Likewise, in Hertfordshire, UK, architects Tate Harmer have created “a new cottage vernacular that’s rooted in the agriculture history of area”, says Harmer. His firm has replaced a bungalow with Kintyre, a low-energy family home that draws on the nearby pared back, utilitarian farm buildings and thatched dwellings, with their low eaves, dormer windows and little gables popping out of the roof. “We started to merge the two elements.”

Instead of traditional roof tiles, he has wrapped the timber cladding of the walls over the entire building. The wood, which will turn silver over time, is made watertight by the rubber membrane beneath. “Materials technology has moved on, and this roof does the same job as tiles,” he adds.

Extreme countryside

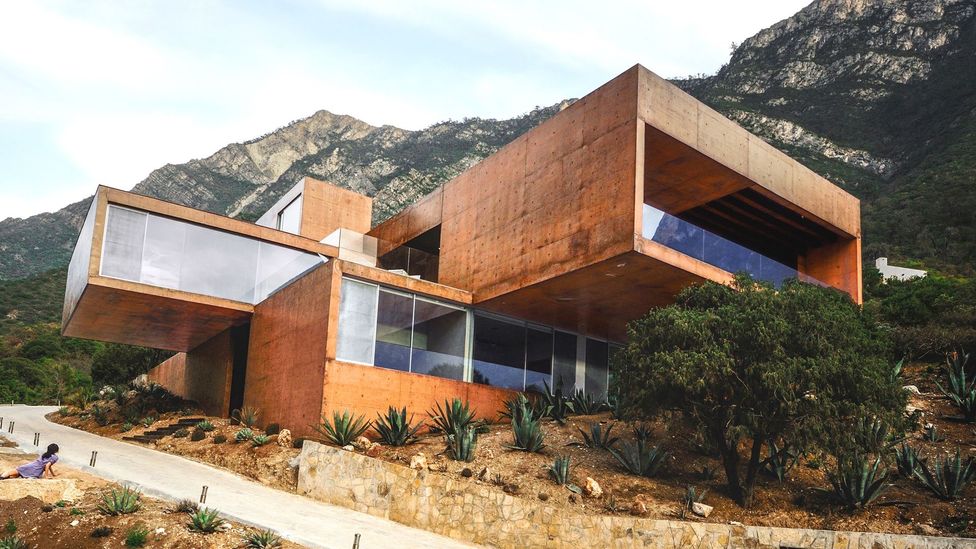

The more extreme the countryside, the more daring the possibilities, it seems. In the Mexican region of Nuevo Leon, Narigua House is divided into three stacked volumes jutting out from the mountainside. Architect David Pedroza Castañeda of local firm P+O describes it as “a stone work humbly placed in an impressive landscape of old cedar trees. It has an incredible landscape that translates to incredible views from inside the house, and specific colours, forms and vegetation that demanded a dialogue from the architectural volumes.”

A really remote location sometimes has fewer regulations, allowing “a lot more liberty in terms of form”, says Castañeda, but he warns that “you can actually do less and not more in rural sites, in terms of technology and access to materials.”

With more room to move, buildings can adopt unusual proportions – Patrick Keane

US architects Olson Kundig used those limitations to their advantage with their Treehouse in the Costa Rican region of Santa Teresa. Built above the Pacific coast and backing on to semi-tropical forest, it’s a three-storey rectangle tower in local timber. The whole building is designed to work passively, and the top and bottom floors are completely open to the elements, courtesy of a manually-operated double-layered screen. Architect Tom Kundig identifies two styles of vacation homes emerging in the area. “Those that are more influenced by Western architecture are likely to be air-conditioned and hermetically sealed” against the wet and dry seasons. Rarer are homes that “embrace the environment and climate”, like the Treehouse.

In Poland, Robert Konieczny of architecture firm KWK Promes has carved a niche creating rural homes that are almost futuristic looking. His By the Way House is on the River Vistula.

“For sure, the idea of this house fits best for a very large area, which is usually inaccessible in a city,” he says. The design is based around a ‘road’, a strip of concrete which then rises and twists to create the building’s ceilings, roof and walls, before finally becoming a footbridge that connects to the water’s edge.

A big plot means architects can play with layout in a way that is impossible on a tight urban site. This was Patrick Keane’s experience in Katoomba, Australia, on the Blue Mountains escarpment. He’s building a cluster of bold, steel-framed modular houses on a hilltop there. “There are things to prioritise like sun angles, however there was a lot more freedom in layout. In a rural context, new ideas or thoughts can be tested and tried out, or ideas that may have not been able to be entertained can be looked at in a rural context,” he says. “With more room to move, buildings can adopt unusual proportions and dovetail this into local cultures and contexts or regional themes, which always provide good building blocks for innovation and excitement in architecture.” Next up for Keane is a beach house in Thailand, which will be even curvier and more unusual.

London architect Sam Selencky points out that these bold projects – in the UK at least – are typically the exception and not the rule, and tend to be one-off houses “where a client has decided to commission an architect who is going to take a proper site-led conceptual design approach to the project”. With its modernist horizontal planes, Selencky Parsons’ River House in Oxfordshire on the banks of the Thames fits the bill.

And while Selencky doesn’t pigeonhole a specific new rural vernacular, he recognises “a movement that is leading to an acceptance and adoption of a more design-led approach to rural houses”, resulting in more exciting projects.

The sleek, horizontal design of Selencky Parsons’ River House is based on a site-led approach (Credit: Jim Stephenson)

For Ludewig, this approach comes from the fresh eye that architects can bring. “For us, there’s something interesting in the condition of not being a local. We notice things that are normal if you’re a local. We’re looking to create something that lives in between, something that’s not outright contemporary-from-nowhere, but not quite what the locals would do.”

But it’s a different story for mass-produced housing in the English countryside. That is still likely to comprise “winding cul-de-sacs of bland houses taken straight from house-builders’ standard range, that make no unique response to their setting or provide their occupants with anything special or unusual”, according to Selencky.

The more extreme the countryside, the more daring the architectural possibilities (Credit: P+O)

Perhaps this is where architects should next turn their attention. Writer Tom Fort thinks so. In his book The Village News – The Truth Behind England’s Rural Idyll, the reader is asked to imagine that Fort has been put in charge of nurturing village life, as the Government’s Village Tsar, or Commissioner for Rural Communities. “As the man in charge of saving the village, I would make it my business to smash the wretched monotony of estate design,” because “the general run of modern housing estates… are boring and bland.” To this end, he would need to recruit “designers and architects who… are bold in their thinking”.

Will these sorts of developments one day join the ‘new rural’ architecture movement?

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List, a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.